Contents、目次

2.Cooking method of staple food、主食料の食べ方 (Part1)

4.Seasoning、調味料

(1)Salt、塩

People in

a mountainous area made an effort to acquire salt. It was said that even a

self-sufficient farmer had to buy salt. Salt has been used to make miso

paste, soy sauce, pickled vegetables or plums, simmered foods and so on. It

was used to preserve fishes in a seaside village. The total consumption of salt

in various areas are written, for example a family of five consumed around 200

liters a year.

山間部の人々は、栄養分としても必須の塩を得るために苦労をしました。自給自足だった農家でさえも、「買う物は塩ばかり」といわれたほどでした。塩は、味噌、梅漬け、漬物、醤油を作ったり、煮物の味付けにも使われます。沿岸部では魚類の塩蔵に使われます。五人家族で三俵などの各地の年間使用量が列挙されています。

(2)Miso paste、味噌

People

made miso paste which is a fermented seasoning by themselves; they ashamed to

buy it. It was also used as a side dish by itself. The photo below is a

typical breakfast in an inn of Gifu Prefecture. We put the roasted miso on the

rice; it goes well with rice.

Sugiyama

(hotel) in Gifu City、岐阜市すぎ山さんの朝食から

買い味噌を恥じるというニュアンスが「手前味噌」という言葉にあったそうです。自家製造でした。なめ味噌としておかずにすることも各地で行われました。朴葉味噌もそうですね。

(3)Soy sauce、醤油

Soy sauce

started to be used much later than miso paste. It spread in around the

18th century. People also made it by themselves. They enjoyed

competing the quality of the homemade products. Its mash was used as a side

dish like miso paste.

味噌と比べると贅沢品で、歴史も浅く、江戸時代からです。各家で作った醤油の披露、品評も恒例で、主婦同士で出来具合を比べたそうです。漉した後のもろみはなめ味噌になりました。

(4)Sugar、砂糖

Ordinary

people in countryside couldn’t use it usually even in the late 19th

century. When they made cakes, they used salt instead of sugar. It was a

luxury item because most of them were imported.

庶民が砂糖を使えるようになったのは遠い昔ではなく、地方では19世紀末でも平素の煮物には砂糖を使わず、団子も塩餡が普通でした。贅沢品でした。国産できるのは沖縄や瀬戸内ぐらいで、輸入品が多かったのです。

(5)Green tea and snacks、お茶やお菓子

The

custom of drinking tea after a meal started in the early 20th

century among people. They usually had a hot water.

Common

snacks were originally nuts and fruits such as chestnuts and persimmons.

Roaster rice, fried beans and arare which is made from glutinous rice were

eaten. Those had been homemade snacks, however people bought them later on.

Commercial foods dated from snacks and nibbles for drinks. I guess the reason

was that people consumed them a little (inefficiency to cook) and could live

without them.

Arare

for Girls’ Festival in March、雛あられ https://ganref.jp/m/teku-teku/portfolios/photo_detail/4848141

庶民が茶を飲むのは、大正時代からで、食後には白湯を飲むことが多かったそうです。ただし、茶粥を常食とする地方では茶を大量に消費しました。飯を食べられないので粥にしたのですが、茶は育ったのですね。

菓子は元々栗、柿などの草木の実(木果子)でした。焼米、煎った豆、あられもお菓子になりました。家々で作っていましたが、食物の商品化は、菓子や酒肴からが始まったそうです。無くてもなんとかなるし、少量ですから買うことにしたのでしょうか。

In the early 18th century, a Buddhist monk complained about the transition of food habits.

(2) We ate nuts or fruits as a snack; they change to dried or steamed cakes.

(4) We drank unrefined sake (alcohol); it changes to refined one.

(5) We cultivated tea leaves; we buy tea leaves made in Kyoto now.

(6) We had roasted beans as a snack; they change to konpeito (a kind of candy)

(7) We cultivated tobacco leaves; now we bought them.

(8) We made miso paste from bran; we make it by grains now.

(9) We had four dishes on a tray at party; two trays are served now.

The monk wrote it was luxury, but

I think it was progress.

天保年間(1830-1844)の越後の僧は、食生活の変化を、万事奢るようになったと嘆いています(『救荒孫の杖))。①焼味噌で食事したのに、吸い物・大平(おかずの椀)を付けるようになった、②木の実・果物が、干菓子・蒸し菓子になった、③焼き塩での味付けが白砂糖に、④濁り酒がすみ酒に、⑤手作りの茶が買った宇治茶に、⑥豆煎りが金平糖に、⑦手煙草が旅煙草(他の産地の物?)に、⑧じんた味噌(糠味噌)が麹味噌に、⑨四つ椀の饗応が二の膳付きに、との変化を記しています。奢侈というよりも、大進歩だと思います。平和な江戸時代に、人びとは豊かになりました。食生活はどんどん変わって行きます。

5.Kitchenware and tableware、食具

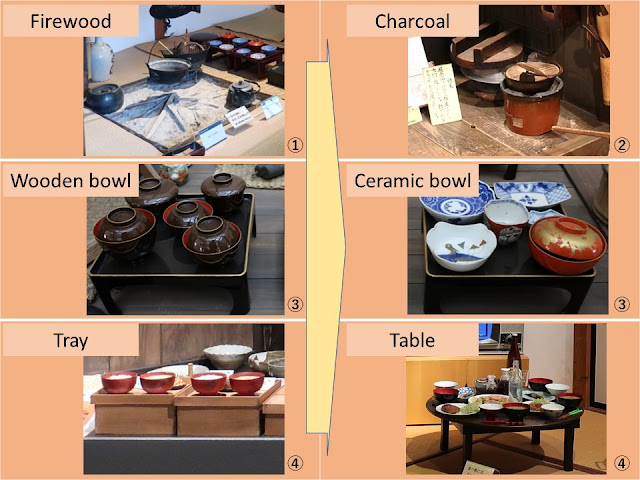

The transition

of utensils is written in this chapter. Major changes between pre-modern

and early-modern era are shown below. A wooden bowls was continuously used as a

soup cup because of good thermal insulation.

Transaction、食具の変遷 ①Former

Yamabe School、旧山辺学校校舎 ②Shitamachi Museum 下町風俗資料館 ③Ten-ei Culture and

Tradition Museum、天栄村ふるさと文化伝承館 ④MAHORON(Fukushima)、まほろん(福島県文化財センター)

臼や鍋などの食具の変遷について書かれています。大きな変化は、①囲炉裏が無くなって、炭を使う七輪で調理するようになったこと、②木椀から手触りが良く明るい色の瀬戸物になったことです。汁椀では断熱性が良い木椀が残りました。③膳から食卓への変化はライフスタイルも変えました。

Bento

box (Lunch box):

Various kinds of boxes were made. Fishermen sometimes packed three or four meals in a box, to be ready for a storm. A woven box was inconvenient for someone

because you couldn’t pour tea into it. A hemp bag was used when you ate crumbly

grain such as hie millet. People pushed the bottom of the bag and ate; they

didn’t need chopsticks.

Tableware

was NOT washed after a meal.

Usual, they just rinsed them, drank rinse water or tea, and put them in a

personal box. They washed tableware in a particular day, especially they

washed completely in the first three days of the New Year. It was not to keep

them clean for themselves, but for a god. In many places, people use new

chopsticks in the New Year’s; it is a relic of the old practice. I also do it.

In some

places, people washed tableware before a festival, on the New Year’s Eve and during

Bon rite in summer. They also washed equipment of a god or Buddha at that time.

Btw, the storage

management of home foods especially grains was a role of a housewife.

Therefore, even her husband or her mother-in-law couldn’t enter the storage.

The wife controlled the food in order to prevent its shortage.

弁当:なんと、弁当の言葉の意味はまだ分からないのだそうです。モチメシ、モチビルという地方もあり、これなら分かりますね。それはさておき、用途に合わせて様々な弁当箱ができました。海に出る人は、悪天候に備えて三食分、四食分持つことがありました。編んだ弁当箱は、軽いが茶漬けができないのが難点、稗飯のような粘り気が少なくこぼれやすい物を入れる地方は、麻袋を使い、袋の底を押し上げ箸無しで食べる、などなどが記載されています。

食器をいつ洗うか:日常は食後の湯茶ですすいで、それを飲んで、箱膳にしまいました。食器を洗うのは決まった日ですが、正月三が日には、椀、茶碗だけでなく箱膳までザアザア水をかけて洗いました。清潔のためでなく、神への清浄のつつしみでした。正月の箸だけは新しくする家が少なくないのも当時の名残です。祭りの前日や大晦日、盆に神仏の祭具と食器を洗う所があります。

ところで、米の保管(食糧の管理)は主婦の仕事で、主も姑も嫁も倉庫には入れませんでした。不足しないように主婦がやりくりしたのです。

Previous

post: Old dietary

habit in Japan (published in 1968) (1/3)、食生活の歴史 part1

Next post: Old dietary habit in Japan (published in 1968) (3/3)、食生活の歴史 part3

Comments

Post a Comment