People

gather in front of the festival float @ Sekinoyama

museum 関の山車会館

Author: Sadao Furukawa、古川貞雄

人の楽しみの発見度: Very Good ★★☆

The book is about holidays in the Edo period (1603~1868)

when farmers comprised 85% of Japanese population. We didn’t use international

calendar at that time, so we did NOT have Sunday.

People had holidays on the New Year’s

Day, at the time of Bon

rite for ancestors, village festivals and so on. Holidays were decided by

each village at that time. The number of holidays were around thirty a year

in the early Edo period. Happily, it was increasing and reached eighty days a

year in some villages.

This book tells us how the holiday was

decided mainly. The author quoted references which are mostly from Nagano

prefecture in central Japan where he is, and he confirmed whether it was common

across Japan. The total number of references is 267; he investigated a lot.

Although he doesn’t focus on how people

enjoyed on holidays, he mentioned what they did. This is a very good book about

holidays around 200 years ago.

Contents 目次

Ⅰ. Real state of holidays、遊びのありよう

Ⅱ. Increasing

of holidays、増大する遊びの日

Ⅲ. Momentum to defeat the regulation、規制をのりこえる潮流 (Part 2)

江戸時代の農村の休日について書いた本です。「休日と若者組の社会史」というサブタイトルが付いています。

江戸時代は盆と正月だけが休日だと思っている方も多いと思いますが、それ以外にも祭りの日などの休日があって、だいた30日ぐらいになりました(村によって休日が違いました)。それが、主に若者達の要求によって増えていきます。「祭りの次の日は休みたい」などなど。80日に達した村もありました。高度成長時代のサラリーマン(週休一日制+半ドン)と同等ですね。

本書では、休日の決め方や日数について、多くの事例と共に書かれてます(引用が267件もあります)。人々が休日をどのように楽しんだかについてはあまり詳しく書かれていませんが、何をしたかは分かります。江戸時代の休日の実態を書いた良い本です。著者が住む信州で調査し、全国的な共通性を検証しています。

Introduction、はじめに

“Holiday” was called “Asobi (playing) Bi (day)” or “Yasumi (taking a rest) Bi (day)” in the Edo period(1603~1868). Interestingly enough, there was a penalty for working on a holiday; it was totally different from the current employment regulation in which we can get allowance for working on holidays.

Btw,

an international calendar (solar calendar) was adopted in 1872 (after the Edo

period), and Sunday was enacted. However, it didn’t spread until the school education became common several decades

later.

江戸時代は、休日は村ごとに決めました。1872(明治5)年に、太陽暦が採用され、日曜日ができましたが、国が定めた休日が普及し始めるのは、学校教育が本格化した明治後半だったそうです。古い話ではないのですね。

休日を、「遊び日」「休み日」「休む日」という呼ぶ地方が多かったそうです。そして、休日に農作業をすると罰則があったそうです。休日出勤禁止。今との大きな違いですね。

Ⅰ Real state of holidays、遊び日のありよう

1.Regular yearly holidays、年間の定例遊び日

The average number of holidays was around thirty a year. In the case of a village in Nagano, festival

holidays including the New Year holidays were twenty-six days, day-off

concerning farming were four days (after rice planting and so on) and a political

holiday on which people celebrated submission of a list of villagers to the government.

Common holidays among villages were

three days during New Year’s, the 15th of January (Ko (little)

Shougatu (New Year)”, three days during Bon

and three days of Sekku (third of March:3/3, fifth of May:5/5 and

seventh of July:7/7).

Each village had its own holidays which

depended on a village festival, agricultural work and so on. There were also

holidays only for men or women.

The author wrote that twenty

to thirty holidays a year were necessary to take a rest and keep a bond

among villagers (festivals and so on).

平均的な年間休日は、年間約30日でした。上塩尻村(現上田市の一部)を例にとると、①「神遊びの日」の原義に近い民俗的年中行事の日が、正月の三が日など26日、②農作業に直接関わる遊び日が、田植明けなど4日、③行政的な休日として宗門改帳の判押し日(4月)が1日です。

村々に共通する休日は、正月三が日、小正月、盆(三日)、三月・五月・七月の節句の合計10日です。七月の節句は、今の七夕ですね。残りは、農業の事情(米作中心か、麦などの他の作物の生産が中心かなど)や社寺の祭礼日で異なりました。また、男女別々の休日もあったそうです。

年間休日は20日前後から30日以内の村が多く、筆者は、農作業の休養と村人の団結を維持するため(祭りなど)に不可欠な日数としています。

2.Activities on holidays、遊び日の生活内容

People were freed from labor. They had a

special meal and enjoyed events which were prohibited on ordinary days.

休日は、労働から解放され、特別の食事を食べ、平日には許されない「遊び」ができる日でした。

(1) Meals

The practice of Kouzu family in Nagano

was introduced. They grew 72 tons of rice a year and hired helpers.

On ordinary days, helpers ate barley, or rice

containing millet. They could eat a lot during a rice-planting term when they worked hard.

On holidays, they

ate white rice which was expensive. Afterwards, the holiday dinner

was changing from rice or mochi cakes to more unusual one: noodles,

manju sweet buns and so on. Japanese didn’t eat meat back then, so it was a treat for them.

Btw, the family members of Kouze ate almost same meals as helpers. But they usually ate high quality miso soup, and sometimes ate an additional dish.

Nerima Shakujiikoen Furusato Museum 石神井公園ふるさと文化館(1)食事

志賀村(現佐久市の一部)の神津家(481石の地主)の奉公人の食事規定が残っています。

平日は、米に黍(きび)を混ぜたり、麦の飯を食べました。田植など重作業の時期は量が多いなど、時期によって五つのパターンがありました。

一方、休日には米だけの飯が出ました。寛政(1789-1801)前後になると、蕎麦や麺類、小豆飯などが出ました。米は神に捧げる貴重な食べ物なのですが、近世後期には食生活が良質化・多様化し、休日(ハレの日)の食事は、米飯・餅から麺類・麦切・饅頭・蕎麦等へと変化しました。

ところで、神津家では、奉公人と家族の食事に大差はなく家族は台所味噌ではなく上味噌(ふすまを使っていない)を常用していたり、時として肴、汁が付いたりする程度でした。

(2)

Entertainment

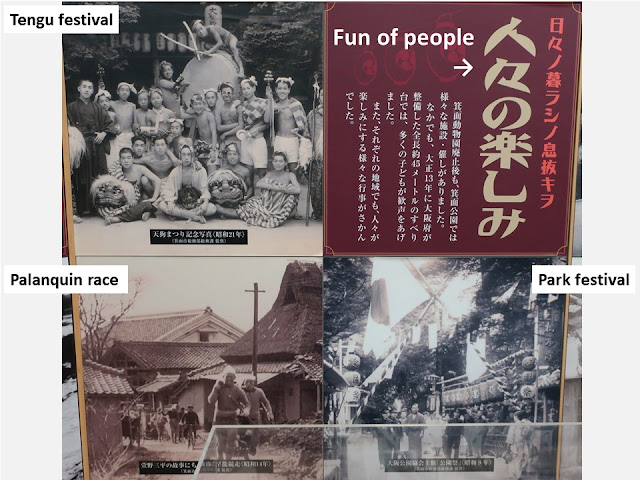

Entertainment during a festival was

the most exciting for people. Japanese festival begins with praying

to a god, then Naorai rite is held in which people eat offering

including sake (alcohol). After that, a fun event starts.

It says that the event was growing and becoming playful since the 18th century. People walked around while carrying a portable shrine, a float, a lantern and so on. Moreover, various events were approved; such as a firework show, a theater, sumo wrestling matches.

The author mentioned, “A festival was the holiday among

holidays. It was the best authorized entertainment for farmers at that time.”

A portable

lantern (behind) and a portable shrine @ NationalMuseum of Japanese History

The festival was run by lads. Every village had an association of lads which was called

“Wakamono (lads) Gumi (group)” (hereinafter, this is called "lads’

group" in this article). They run the festivals under supports of the

designated middle-aged men and under the approvals of the village officers who

were also farmers.

The group interacted with other lads’

groups, and organized a big event sometimes. Two cases in Nagano were cited as

follows.

At the festival in 1852, the group planned

Kabuki performance. They invited four teachers, practiced for a hundred

days and gained lumber in order to make a stage. They invited eight lads'

groups from other villages, and held three-day performance. Plus, they served

meals and sake for the guests.

In the festival of the other village in Nagano, they held “Chushingura” which was the same themed play as “47 RONIN” (American movie). During two days, more than ten lads’ groups came with gift-money, and four hundred people came from more than thirty villages including neighboring prefecture. Given it was held in the unfree feudal era, I can say it was really huge and daring event.

However, the

event was in the red, unfortunately. The cost was 43 ryo (around $43,000) and the loss was 28

ryo (around $28,000). The debt was split by twenty-five lads. The author

praises their enthusiasm and great efforts.

Stage performance @ Minoh museum 箕面市立郷土資料館

(2)遊興

遊興は、何といっても祭りの時の遊びです。祭りは、神祭り、直会、饗宴の三部構成ですが、18世紀以降は饗宴の部分が「遊興化し肥大化する」と書かれています。神輿、山車、燈籠などの練りだし、花火、芝居・相撲等の興行も晴れて催せます。「祭礼こそ、遊び日中の遊び日、近世農民の公認された最大の遊興にほかならない」と筆者は書きます。

祭礼の担い手は若者で、若者組が主体となり、後見人格の中老・中年寄の保証と指導の元に、村役人の承認を取り付けて行われるのが通例でした。祭りを仕切るのは若者組でした。

若者組は、近隣の村の若者組と交流し、大きなイベントも催しました。

三日市場村(現飯田市の一部)では、1852年の祭礼で、狂言(歌舞伎)の興行を試み、師匠四人を招いて100日間の練習を積み、村の許可を取り、舞台用の材木を手配しました。三月節句を中日に三日間上演し、近隣八集落の若連中を招待するとともに、見物人を酒食でもてなました。

また、海尻村(現南牧村の一部)の祭礼では、忠臣蔵などを二日間演じ、10か村以上から若者組が花代を持参し、甲州を含む三十余村から観客400人が押しよせました。総費用は43両で、28両が赤字になってしまいましたが、若者25人が割賦負担してました。「多額の経費まで、若連中がかせいで捻出したことも思いあわせれば、若者たちの熱意と労力は大変なものがある」と書かれています。

Ⅱ Increasing of holidays、増大する遊び日

1.Increasing of festival holidays、祭礼遊び日の増加

Along with the improving of agricultural

productivity, villages had leeway to increase holidays. The best reason to do

so was to enshrine a new deity which prevented villagers from fire, disaster

or plague. In Japan, a Shinto deity is divided and is transferred to a new

location. The popular deity was Akiba and Konpira at that time.

Fukuzawa family in Nagano recorded the annual events. There were 26 to 27 holidays (four half holidays were included) a year in the first half of the 19th century. Three new holidays which were added during the period were all Shinto festivals including Akiba shrine’s one.

The thing was that ten holidays were added in 1849. Moreover, a weather festival was added in the case of a long spell of rain. The author wrote that Fukuzawa probably could not suppress the employees’ requirement.

In Nagano, festival holidays were

increasing. In the mid-19th century, more than half of villages had

30 to 39 holidays followed by villages which had 40 to 49 holidays. There was a

village which had more than 50 holidays.

Talking about all over Japan, the

number of holidays seemed to be thirty to seventy at that time. Most of new

holidays were relevant to festivals which included day off after rice-planting

and harvesting.

農業の生産性の向上に伴い、休日を増やす余裕がでてきました。良い理由が、火除け、厄除け、病除けなどのご利益のある神様の新規勧請でした。近世中後期には、秋葉社・金比羅社の勧請が広まりました。

赤須村(現駒ヶ根市)の福沢家の行事帳が残っています。天保(1831-1845)のころの休日は26~27日(うち4日は半日休日)でした。そのうち三日が増加した休日でした。2月15日の船山秋葉祭り(秋葉神社)、3月15日のおくわ祭り、6月28日の日本祇祭りです。日本祇祭りの内容は不明ですが、おくわ祭りは、「御鍬送り」という木製の鍬をご神体として村から村へと送る祭りで、五穀豊穣を祈念する伊勢信仰の一つです。中部地方で広まりました。さらに、1849年に10日の休日と、雨天続きの場合に天気祭りが加えられています。福沢家は、奉公人や小作人の力を抑えられなくなって休日が一気に増えたのではないか筆者は考察しています。

信州では、神仏祭礼日が増え、幕末の年間休日数は、30日台が過半を占め、40日台が続き、50日台前半の村もありました。

全国的には、「年間日数にして30日台から多くて50、60日台程度のようである。そして、増加する遊び日の内容的性格は、田植休み・収穫祭等をふくめ、神仏事祭礼遊び日の拡大、新設を基本としている」と書かれています。

2.Increasing of days of rest、定例労働休日の増加

The number of days of rest depended on the

regions.

Although a few villages had rest days in

Nagano, Ohkurazaki village had four rest days a month (3, 16, 24 and 28)

which were not related to festivals; farmers just took a rest. They had fifty

holidays a year.

The number of days of rest in various

areas are written subsequently.

In Niigata, a village had a special day off or a half day off on a rainy day after a dry weather. Village officers who were also farmers decided it and informed villagers. During Doyou period in summer, if dry weather continued for five days, they took a day off. Because it was a sign of good harvest.

The 17th of July was the

additional holiday after Bon period. It was interesting that villagers could

continue Bon dance on the day, if good harvest was expected and the village

head approved. I think it’s too early to expect good harvest because it’s before

the typhoon season. I can imagine the villagers who enjoyed an additional Bon

dancing. People loved dancing so

much back then. It was also an encounter for boys and girls.

Bon

dancing near my house

In Shounai region, Yamagata, surprisingly enough, people took a day off after working for seven days straight from February to July. From August to November, they did it after working for ten days. It was decided by Shounai-han (local government), not a village. I know the 1st and the 15th were days of rest in some villages, but I was surprised with the rule. It's similar to Western calendar, and the number of days off were not so different from the one in 1970s.

Btw, Sendai-han approved eighty

holidays in 1805 which was twice of the first half of the 18th

century. It was due to the specific reason: labor shortage in the region. In order

to call in helpers, Sendai-han proposed good wage, many holidays and light work

to them.

純然たる労働休養のための休日の増加は地域差がありました。

信州では純労働休日の例は少ないのですが、大倉崎村(現飯山市)では、遊び日と休日を区分し、毎月3、16、24、28日の休日にしました。祭礼とは関係ない労働休日です。休みの年間合計は50日になました。

次に、全国各所の労働休日の例が記載されています。越後国浦村(現越路町)では、6月に、日照りが続く時に雨が降れば、庄屋・役人が触を出し、一日或いは半日休日にしました(露気休み)。また、土用入りの頃ですが、五日目に雨がなければ豊作の兆しとして休日にしました。7月17日は、盆流れの休日でしたが、「豊作と思はるる作柄なれば、庄屋の許可を得て今夜も踊をなす」としました。台風シーズンの前なので、豊作を祝うには早いと思いますが、追加の盆踊りを楽しむ人びとの姿が目に浮かびます。

1660年の庄内藩の布達では、なんと、2月から7月は、7日働いて8日目に、8月から11月までは10日働いて11日目に労働休日をとれと規定しています。1日、15日の定例休日が多かったそうですが、これはすごい。高度成長時代と変わりません。

ところで、仙台藩では、1805年に80日が公認の全休日になりました。享保(1716-1736)年間の40日から倍増です。興味深いのがその理由で、仙台藩は人手不足なので、「高賃金・多休日・緩労働の好条件をもって他領の奉公人を誘致している」と筆者は指摘しています。

3.Negai (pleaded) holiday and Katte (selfish) holiday、願い遊び日・勝って遊び日

Although the holiday was decided by village officers, afterwards, it was decided at the general meeting of farmers who were farm landowners in the beginning of the year. Holidays which were affected by climate such as a post rice planting day off were decided by the officers and informed.

Moreover, villagers pleaded with officers to make a particular holiday. Such kind of holidays became to a regular holiday later on. Those were called “Negai (pleaded) holiday”, and increased in around 1800 across Japan. In a village in Nagano, the number of holidays reached fifty-one. The officers concerned the decrease of harvest, and made a rule to prohibit “Negai holiday”.

On the other hand, “Katte (selfish)

holiday” emerged on which villagers didn’t plead a holiday but they took one.

- Increasing of agricultural productivity

- Demand of villagers to have leeway to enjoy their lives

- It’s clear that helpers asked the increase.

- Festival holidays were probably required by its attendees. He assumes that villagers who were not engaged in agriculture asked a lot. They were craftsmen, peddlers and so on.

- Lads.

The demand of lads in

Nagano was written in the village head’s diary elaborately. Lads required

holidays in various reasons; celebration of rain, beginning of Higan

season, completion of cotton planting, start of the practice term for the

festival, cleanup after the festival, settling down of the trouble with the

other village and so on. Lads went to the head’s residence and put pressure on

him. It was a common issue among villages.

Village officers and lords (samurai)

made a regulation in order to counter lads’ behavior. The author mentioned that

the requirement of lads and lower-class farmers made new holidays at the

end of this chapter.

Yokohama History Museum 横浜市歴史博物館

休日が増大した近世後期になると。村役人が休日を決定する段階から、毎年の総百姓の年頭の寄合で決められる段階になりました。田植休みなど動く要素がある日は村役人が決め、触れを出しました。

さらに、「願い遊び日」「不時遊び日」「流行り遊び日」という村人が村役人に願い出た遊び日の定例化が進みます。願い遊び日は18世紀末から19世紀にかけて全国各地で増えました。信州の桜沢村(現中野市)では、年間休日が51日になってしまい、「村方衰微之基」として1813年に願い遊び日を禁じる取り決めをしています。

そればかりか、村役人に願い出ない「勝手遊び日」がではじめます。

①生産力の増大による労働日当りの収益の増加、

②労働に明け暮れることにあきたりない農民のゆとりある生活への希求、

をあげています。

①奉公人たちの要求があったことは明らかである

②祭礼型の休日は、祭りの担い手が要求の主体と考えられる。特に、江戸時代後期に現れた農作業に専念していない村民(職人・小商人・日雇・雑業等)が要求したと推測できる。

③若者衆の要求。

若者衆の要求は、井上村(現須坂市)の名主に日記は、生々しく記されています。若者衆は、彼岸の入口、雨祝い、木綿蒔き相済み、祭礼稽古始め、祭礼後仕舞い、二百十日、他村との出入り相済みなど何かにつけて休日を要求しました。「若衆多数参り」圧力をかけています。他の村の若者衆のパワーを示す例も書かれています。

これに対して、村役人や領主も規制を出しました。筆者は。下層農民とともに「若者層の要求が、いたるところで遊び日増大を生み出していたという事実を確認しておきたい」と本章を結んでいます。

Previous

post (Local museum in a former pioneer village):

Next

post (Second half of the book; Momentum

to defeat the clampdown/規制をのりこえる潮流):

Village

holidays in the Edo period (2/2)、村の遊び日 (2/2)

Comments

Post a Comment