Contents 目次

1. Nishijo village and Nishimatsu family、西条村西松家の周辺(Part 1)2. Life in river island and river improvement、治水と輪中の暮らし(Part 1)

3. Activities as a village head、庄屋としての活動(Part 1)

4. Necessities of life (food, clothing and

housing) and annual events、衣食住と年中行事(Part 2)

5. Diseases and death、病気と死亡(Part 3/this

article、この記事です)

6. Women and helpers、女性たちと奉公人(Part 3/this

article、この記事です)

7. Fun concerning hobbies、趣味の世界(Part 4)

8. Village budget, cost of living and price

fluctuation、村入用・生活費・物価(Part 4)

Chapter 5 :Diseases and death、病気と死亡-江戸時代の医療事情-

1.Death of babies and difficulty of giving birth、乳児の死亡と出産難

The

author hypothesizes that the high mortality rate of babies made people recognize the

frailty of life. It

would also link not to value life so much.

Gonbei’s

father went to a table game (shougi) event when his baby died. Even in

the case of stillbirth, they celebrated the seventh day after the birth. The

author assumed it was held as the celebration of the safety of the mother. It

is too much different way of thinking from recent one.

*Gonbei was the village head. He wrote the diary and recorded his life.

Edo-Tokyo Museum 江戸東京博物館

筆者は、「乳幼児死亡率の高さがもたらす死の考え方が、命のはかなさへのある種の達観を生み出し、それはまた、人々の意識の中で命の軽さと結びついていたといえないだろうか」と書いています。

何しろ、この日記を書いた庄屋の権兵衛の父は、赤子が死んだ翌日から将棋大会に出かけたのですから、乳児の死を当然のことと考えたようです。また、死産でも七夜祝いが行われています。筆者は、母親の無事を祝ったものだと考察しています。今とは感覚が違いますね。

2.Smallpox and measles、疱瘡と麻疹(はしか)

Before

smallpox vaccination spread in the late 19th century, people relied on

superstition. For example, rice water was poured to a measles child.

Gonbei’s child died by measles. Later on, he

made his children get vaccinated.

立川昭二は江戸時代を評して、「疱瘡の子供とその家庭をめぐって、神社・物売りなどと人びととのぬくもりが伝わる時代であった」と書いています。

それはさておき、日本で種痘が広まるのは19世紀後半で、加持祈祷が治療の中心でした。例えば、回復後の膿瘡が器量にさわらぬことを願って、米のとぎ汁をかける「ささ湯かけ」が行われました(目的は筆者の推測)。なお、権兵衛は疱瘡で子供を失っており、その後は種痘を受けさせています。

3.Disease of Gonbei and his family、権兵衛と家族の病気

Gonben’s

son Kensuke died at twenty; he was supposed to be a successor and was educated

as a village head. How Gonben took care of Kensuke is written specifically such

as medicine and faith-healing. He lost consciousness while he stood under a

waterfall, which was a therapy. It’s sad.

Kensuke’s younger brother caused hearing loss.

Gonbei bought a hand-operated electric generator “Erekiteru” which was a

cutting-edge medical equipment. However, the electric shock didn’t work.

Erekiteru、エレキテル The National Museum of Nature and Science 国立科学博物館

権兵衛は、庄屋見習いをしていた息子・謙介を20歳で失っており、その手当(祈祷や施薬など)が極めて具体的に書かれています。謙介は、養老の滝に打たれているときに正気に戻らなくなったといいますから悲しいです。難聴だったその弟には、エレキテルを買いました。電気ショックによる機能回復でしたが、効果はありませんでした。

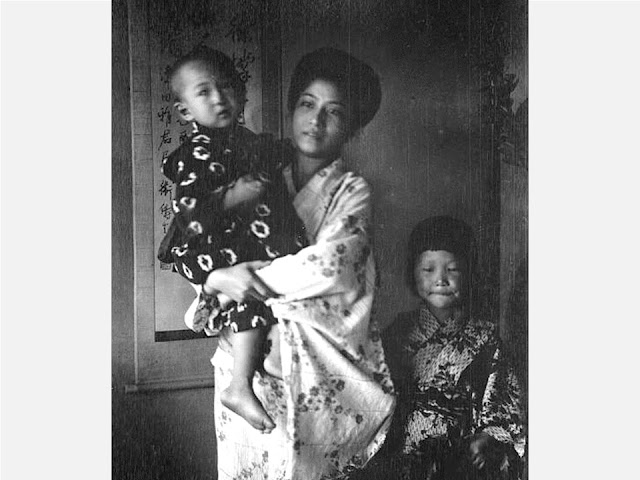

Chapter 6: Women and helpers、女性たちと奉公人

1.Women of Gonbei’s family and their marriages、西松家の女性たちとその結婚

There

are few descriptions of women; only several people are written in the diary.

However, the custom interested me.

(1)

Gonbei’s half-younger-sister “Koma” stayed at her fiancé’s house for five

months, then got married. It was a trial marriage which is popular in

Sweden, but is a new practice in Japan now. Koma changed her first name

to Kiku after the marriage. It is an unfamiliar custom for foreigners to change

name.

(2)

“Fumi” who was also Gonbei’s half-younger-sister got married at twenty, but she

divorced seven months later. She got married again at twenty-six. The fact that

her husband was a samurai officer of Knou-han (local ruler) surprised me

because they were in the different social class. It was not bad business

for a not-so-rich samurai to got married with a wealthy farmer’s daughter

because of food assistance and financial support. Fumi upgraded. She also

changed her first name.

(3)

Gonbei’s second wife “Shou” got married when she was twenty; she was fifteen

years younger than Gonbei. She gave birth to four children. The author wrote

that she seemed to live freely.

She often went to her parents’ home, sometimes

went to travel with her sisters and nieces. She liked to go to theater, too. I

guess the big reason was that Gonbei’s mother (mother-in-law) had already died.

The

author mentions her grandmother in the afterword, who was from a village head

family. She never cooked and never instructed servants. She spent her time to

talk with visitors and read books. The author wrote “I can understand Shou’s

behavior well.” It was a fact that there were farmers like aristocrats.

(4)

Gonbei’s daughter “Kita” who was born when he was forty-five: She took a

husband who was a successor of Gonbei. Gonbei searched for a good gentleman;

he checked much information about candidates. The finalist lived in Gonbei’s

house for a year, then he officially got married with Kita. It was also a trial

marriage. The couple made five boys and seven girls, and Nishizawa family

(Gonbei’s family) continued.

https://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/agc/item/2018719561/resource/

日記には女性の記述は少なく、数人について書かれています。でも、興味深いです。

(1)

権兵衛の異母妹のこま:嫁ぎ先の客分として五ヶ月過ごした後、祝言をしました。お試し同棲ですね。また、嫁入りを機に、「きく」と名を変えました。日本人が名前を変えるのは、外国の方には理解しにくい慣行です。

(2)

こまの三歳下の妹、ふみ:20歳で結婚しましたが、七ヶ月で戻ってきました。26歳の時、加納藩士と結婚し武家になりました。こまは八重に改名しました。武家らしい名前ですね。当時の武士は暮らし向きが厳しく、食べ物や金を支援してくれる富農から嫁を迎えるのはメリットがあったそうです。

(3) 権兵衛の後妻のしよう:20歳で嫁いできました。権兵衛とは15歳違いです。しようは四度出産しました。筆者は、「かなり自由に楽しんでいる感がある」と評していて、実家にはしばしば戻り、実家の姉妹や姪と旅に出かけることもありました。芝居も好きでした。権兵衛が認めていたことと共に、姑が居なかったことが影響しているのかも知れません。

「あとがき」に、庄屋出身の筆者の祖母は、一度も台所仕事をせず、家事の指示もせず、「奥の人」として客人の相手や文芸書を読むことに時間を費やしていたということで、「権兵衛の妻の振る舞いがよく理解できる」と書いています。貴族みたいな農民もいたということですねえ。

(4) 権兵衛が45歳の時の娘きた:西松家の跡継ぎとなる婿養子を迎えました。縁談は多数あり、権兵衛は家柄や人物の情報を収集し、比較をしています。婿殿は、まず、客分として迎えられ、1年後の春に正式披露が行われました。これもお試し同棲です。きたは、五男七女をもうけ、西松家を存続させました。

2.Helpers of Gobeis’s family、西松家の奉公人

Half

of his villagers had experience to work as a helper. Some of them had worked in

other villages. Wealthy Gonbei’s family usually hired several helpers.

Half of them were women. They usually served for around two years.

They

caused troubles such as fights of course. It was interesting that some

of them went to Ise Shrine

without approval, where was the most popular destination back then. It took

eight days for the round trip.

Kiyo

did it in 1822 when she was twenty-three, however she wasn’t fired and worked until

twenty-five. They brought a ladle which was a sign of a pilgrim to Ise Shrine. People

on the way, donated them food or money. They usually wore a white kimono

(dress), gaiters, a bamboo hat and straw sandals; it was standard outfit of the

pilgrim.

Gonbei’s eldest son also did it. He went to

Ise Shrine in January of 1853; Gonbei got very angry with him. However, his son

got ill easily and died in September of that year unfortunately. I understand

how much he wanted to visit Ise.

Five millions of pilgrims went to Ise Shrine in 1830、500万人が訪れたという文政13年の伊勢参り Ise Furuichi Sangu-kaido Museum 伊勢古市参宮街道資料館

The ladle above was used in 1830、文政13年の柄杓 Ise Furuichi Sangu-kaido Museum 伊勢古市参宮街道資料館

西条村では、男女とも半数が奉公経験を持ち、他村に奉公に出る人も多い村でした。裕福な西松家では、常時数人の奉公人を雇いました。男女半々で、平均二年の年季奉公でした。

面白いのが、奉公人が引き起こす不始末の中に、喧嘩だけでなく「ぬけ参り」(往来手形なしの伊勢参宮)があることです。西条村から伊勢までは往復で八日ぐらいであり、遠くありません。

1822年にぬけ参りをしたきよは、23歳でした。しかし、暇を出された様子はなく、25歳まで奉公しています。彼らは、柄杓を持って、粥や金銭の施しを受けながら伊勢へ向かいました。白衣姿で笠に脚絆、草履がお決まりのいでたちだったと書かれています。

20歳で夭逝した権兵衛の息子、謙介もぬけ参りをしています。病がちでしたが、1853年1月、ぬけ参りをし、八日目に戻ってきています。権兵衛は激怒し、叔父の取りなしで家に戻ることを許されました。この年の9月に謙介は亡くなっており、謙介の伊勢に行きたい気持ちが良く分かります。

In

1825, Gonbei called Yoshi’s parents to his house and told them that he would

fire her because of bad behavior including staying out late at night.

Helpers were mainly young men and women, so various things happened.

Btw, helpers took a leave and returned to home town several times a year: after the New Year’s, after the rice planting and so on. Helpers went to festivals with Gonbei’s family or other helpers. There were not TVs nor smartphones, so they had much more opportunities to enjoy pastime with people.

https://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/agc/item/2018719661/resource/

1825年、よしは、「不届きの事有り、夜遊びに出」ということで、親を呼び出して暇を申し渡されました。若い男女の住み込みですから、色々起こって当たり前ですね。

奉公人は、年に数回の休暇をもらって在所に帰りました。正月七日、田植の終了時などです。その他、主人の家族と祭りに一緒に出かけたり、奉公人同士で大垣などの祭礼に行ったりする息抜きもありました。テレビもスマホもないので、誰かと遊ぶことが多いのが今との大きな違いです。

Previous post (Part2 of this article、この記事のパート2):

Rural society in the Edo period and

life of the village head (2/4)、庄屋日記にみる江戸の世相と暮らし (2/4)

Next post (Last part of this article、この記事の最後のパート):

Rural society in the Edo period and

life of the village head (4/4)、庄屋日記にみる江戸の世相と暮らし

(4/4)

Comments

Post a Comment